Hong Kong’s in SHOCK

Hong Kong is obsessed with looking good. The city has perfected the art of surfaces, from skyscrapers that tower over its 7.5 million inhabitants to murals that make bar lines on Peele Street longer. But, in between the cracks of this polished exterior lives a subculture of artists and rebels that refuse to play along. They are a part of Hong Kong’s rising graffiti scene. Community members trade Art Basel tickets and shared studio spaces for stolen spray cans, late-night scrawls, and bubble-letter tags slapped across metal shutters.

Hong Kong is obsessed with looking good. The city has perfected the art of surfaces, from skyscrapers that tower over its 7.5 million inhabitants to murals that make bar lines on Peele Street longer. But, in between the cracks of this polished exterior lives a subculture of artists and rebels that refuse to play along. They are a part of Hong Kong’s rising graffiti scene. Community members trade Art Basel tickets and shared studio spaces for stolen spray cans, late-night scrawls, and bubble-letter tags slapped across metal shutters.

Hong Kong's culture of graffiti artists and writers aren’t asking for applause or permission. As the city’s mural industry explodes, filling popular streets with glossy, commissioned walls (mainly from international artists), the local street artists and graffiti writers have drawn a hard line between what is real and what is just decoration. At the center of this is SHOCK, a Hong Kong native whose tag can be seen down virtually any alleyway, across every bridge overpass, and slapped onto the sides of trucks barreling through Mong Kok. SHOCK’s red and white throw-ups (a.k.a. throwies) are raw and impulsive, acting as a reminder that while Hong Kong keeps trying to reinvent itself as a prestige global art destination, there are still people here who would rather burn that whole narrative down than let it flatten who they are.

A core difference between graffiti writers and street artists is that graffiti writers don’t consider themselves artists. Graffiti is a letter-based form of expression, and participants hate being confused with muralists and street painters. “I was never good at drawing. I hate drawing, but in school, I liked scribbling in class and started writing SHOCK on my desk, and it felt good.” SHOCK shared in an interview about how they started their journey into graffiti.

International graf writers and muralists often learn SHOCK’s name the hard way—by accidentally painting over their work. In graffiti, rule number one is don’t cover someone’s piece unless you’re asking for a response. If someone breaks this rule, their piece is covered in revenge tags, a response made half out of spite and half out of principle. Revenge tags are unfastidious but deliberate throwies that SHOCK takes very personally: “I will cover up people's work until they quit painting. That’s also why I have a lot of street credit.” One muralist who covered SHOCK’s tag earlier this year now pays the notorious writer in spray paint before the muralist puts a new piece up. It’s a kind of street-level restitution, an offering. A recognition that in Hong Kong, graffiti writers like SHOCK aren’t just some punky background noise. You respect the lineage, or you answer to it.

The irony is that most muralists, especially the local ones, get it. The “beef” between muralists and graffiti writers isn’t really about turf but more about respect. According to Hong Kong muralist Kris Ho, “respect in street art comes from being so good no one dares touch your work.” Being ‘so good’ in graffiti subculture is not defined by technique or artistic talent. In graffiti, it is quantity over quality. The goal is to have your tag up on as many places as possible; the more inconvenient for the police to take down, the better.

SHOCK carves out their own world in a city that is trying to create a more cohesive and internationally palatable art market. Their tags create a new value on surfaces that traditionally have none. Unlike traditional artists seeking validation from gallerists or paid gigs, SHOCK collects feelings and fragments of themselves and leaves them for the city to deal with. “However the fuck we are feeling, we let people know,” they tell me.

Graffiti’s accessibility stands in stark contrast to Hong Kong’s exclusive art scene. Once a single drop of paint touches a wall (whether it be by a spray can, bucket of paint, or a cheap marker) you become a layer in the city’s visual archive. Anyone can participate. Anyone can speak. And that terrifies the structures that rely on gatekeeping to define what counts as art. Ho explained that in Hong Kong, “people can’t relate art to a profession. There is a traditional mindset that is pushing people traditional mind set that is stopping people to get into the industry or learn art.”

Graf writers like SHOCK are the ones refusing to let commercialization swallow culture whole. Graffiti tags are emotional disclosures in a city that discourages them, symbolizing something all Hongkongers understand but rarely say out loud: the grief of watching a place become unrecognizable and the urge to be seen before you disappear. Relentless tagging forces a kind of coexistence: every mural that is hit changes meaning, shifting from paid decor to contested territory. Every throw-up demands that we stop curating our lives long enough to actually feel something.

Hong Kong Film Festival KEEP LOOKING? Review

Anna Ieong’s debut short, KEEP LOOKING?, is a ruthlessly chaotic ode to the mess of filmmaking itself, depicting a cinematic crashout of a director, Chan Fei Hong (Endy Ieong), his crew, and just about anything that can go wrong on a film set.

Anna Ieong’s debut short, KEEP LOOKING?, is a ruthlessly chaotic ode to the mess of filmmaking itself, depicting a cinematic crashout of a director, Chan Fei Hong (Endy Ieong), his crew, and just about anything that can go wrong on a film set. The premise is simple: a director loses his camera’s memory card, and the crew spirals into a wild hunt to find it. But beneath this straightforward plot, writer and director Ieong cleverly unpacks the emotional tension and fragile egos that drive creative collaboration. What begins as a comedy of errors slowly unravels into a biting critique of gender and power dynamics in film production.

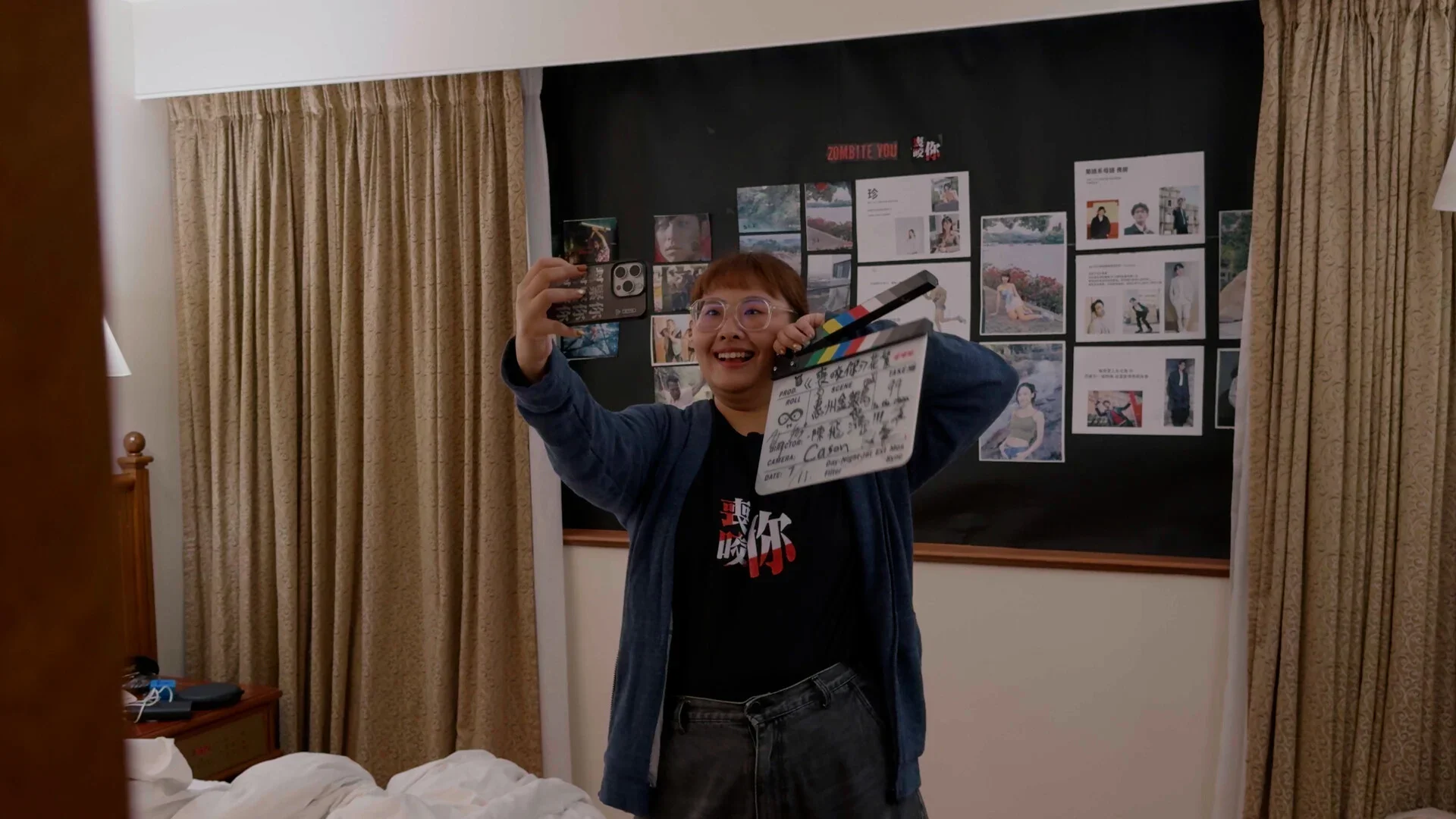

Shot entirely on an iPhone from the perspective of the director of photography, Cason Tam, the film’s opening feels like a family vlog. The audience is placed into a cramped hotel room littered with takeout containers, half-smoked cigarette packs, and empty beer bottles. This is a familiar scene for anyone who’s ever been part of a newly wrapped indie shoot. The crew celebrates the end of their zombie film ZomBite You.

Ieong has plenty of fun in directing the over-dramatic and absurd reactions of her characters. Following in the director's manic footsteps, the crew tears the room apart. The producer is ripping tissues from their box, the lead actor (Ernesto de Sousa) is checking air vents, while the lead actress (Marceline Ma) is calling a psychic for spiritual guidance. The handheld cinematography, jagged cuts, and basic editing creates a frantic, documentary-like realism. As a student film, Ieong proves you don’t need fancy equipment or studio polish to capture the fever dream of filmmaking.

The emotional climax belongs to Vicky (played by Vicky Tong), the overworked script supervisor who's been taking the engetical brunt of the production since the beginning. Her monologue, equal parts rage, exhaustion, and love, lands like a gut punch. The silent reaction of her fellow crew members shines light on the hypocrisy of the film industry, where men’s meltdowns are coddled and romanticized as artistic suffering, while women’s frustrations are dismissed as hysteria with no resolution.

The story ends as abruptly as a shoot day gone wrong. Leong’s satirical lens on filmmaking brilliantly depicts the absurd passion that drives artistic creation. KEEP LOOKING? is a must-watch for any creative in need of a reality check (and a laugh) about the beautiful mess behind the movie industry.

Artist profile - Jenny Jiang

My introduction to Jenny Jiang’s “Sowing Day” exhibition was nothing short of bold. Lying horizontally on a human-sized heap of white cotton fluff, I watched as a man began to cover her stomach in soil. Close-up shots trace his hands as they amass dirt onto her belly. Jiang’s skin shifts and tightens under the weight. Then came the pig's blood. It flowed in deep crimson waves across her body, staining the cloud of cotton beneath her. The camera lingered on Jiang inhaling the metallic scent, which seemed to be filling the air around her.

My introduction to Jenny Jiang’s “Sowing Day” exhibition was nothing short of bold. Lying horizontally on a human-sized heap of white cotton fluff, I watched as a man began to cover her stomach in soil. Close-up shots trace his hands as they amass dirt onto her belly. Jiang’s skin shifts and tightens under the weight. Then came the pig's blood. It flowed in deep crimson waves across her body, staining the cloud of cotton beneath her. The camera lingered on Jiang inhaling the metallic scent, which seemed to be filling the air around her.

To the contextless eye, one would be confused and perhaps uncomfortable watching what looks like a grotesque mummification of snowwhite from her poisoned, death-like sleep. As an audience member, I questioned how this unhinged theatrical was political commentary on the Three-Child Policy in China. Women’s reproductive autonomy is not a new topic of political conversation. As China faces population decline, the government has changed its previously enforced one-child limit to a three-child policy. Many people living in China do not talk about the implementation of this policy in their lives.

Jenny Jiang, a forthcoming performing artist from Hunan Province of China, is unafraid to use her body and creative resistance to depict the impact of such structural systems on women. Through her art, she visualizes what it feels like to navigate life as a woman constrained by government policy. Jiang's work, a two-part video installation, was selected as part of the HKFOREWORD25 exhibition in the 10 Chancery Lane Gallery in Hong Kong. Due to the sensitivity of her work, she rarely exhibits in mainland China.

In an interview with the artist, I got a better understanding of her artistic presence and process. Her demeanor, shy and soft-spoken, was a striking contrast to the boldness of her blood-soaked performance. “When I work, I’m quite different from my personal self,” Jiang shared. “In daily life, I’m introverted and avoid socializing, but when working, I’m forced into social situations and anxiety.” She explained that ‘Sowing Day’ began as an exploration of subconscious dreams, with its current theme emerging as she traced connections between psychology and social systems. The performance was done with a few friends in an abandoned dye factory in Guangzhou. The live audience witnessed the artist’s physical unease under the weight of plasma-drenched soil with flies swarming to the exposed blood. That visceral discomfort became part of the piece. “Cotton, to me, represents softness and feminine power, but when soaked in blood it becomes heavy and suffocating.”

“But why pig’s blood?” I asked.

Jiang laughed and shared that when she told her professor she wanted to use pig’s blood, they were also concerned. “I used pig’s blood intentionally to evoke a sensory reaction from the audience, especially through smell. I see the current Three-Child Policy as distinct from earlier one-child or two-child eras – women’s thinking has advanced, become freer, but the system hasn’t caught up. The pig’s blood symbolizes that contradiction – both fertility and resistance.”

I poked more about her drive to rebel. “My choices have always felt like acts of rebellion against my father from schools to majors…My family doesn’t really understand or support my art,” she admitted. She keeps her work separate from her family, yet still deeply cares about their opinions. They often think her art is “too much” and worry about censorship or public reaction, even though she is careful about what she publishes on mainland platforms. “I want to break away from the system. I know I can’t escape it entirely.”

“I wanted to use performance or installation art to express what can’t be said directly, to reveal the silenced parts.” Performing arts are the perfect medium for Jenny. “Sowing Day” feels like I am watching a young artist recognize her own body for the first time, familiarizing herself with her own form, and understanding herself more deeply. Jiang’s work isn’t about explaining or teaching, but about evoking an experience and using art as performance to embody the state of things.